Published April 2022

Record number of suicides in NC jails: Drug-related deaths, inadequate access to medical care also on the rise

Executive summary and background

More people have died by suicide in NC jails than any other cause, vastly surpassing national averages. These deaths are preventable, yet the numbers rise almost every year. In 2020, NC jails saw the most deaths by suicide – 21; this in the same year new jail regulations required suicide prevention programs.

Disability Rights North Carolina (DRNC) has been monitoring deaths in jails since 2013. In 2017, DRNC released a report of our 4-year study of jail deaths, to draw attention to the alarming increase in suicide deaths in NC jails from 2013 – 2016. In DRNC’s recommendations, we urged county sheriffs and state legislators to require improved response from jails when people are in mental health crises, and to address the gaps in oversight leading to these deaths.

DRNC issued an updated report in 2019 that showed these trends continuing during 2017-2018. State agencies did not adopt any of DRNC’s recommendations from the first report, and suicides and death by overdose in jails continued to increase. The following year, 2019, saw even higher rates of jail deaths by suicide and overdose. DRNC released this information in our 2020 update report, and again urged the adoption of vital jail reforms to prevent future deaths.

Now, in March 2022, DRNC is issuing our analysis of 2020 jail deaths and the number of deaths due to suicide have increased yet again.

Suicide and substance use deaths in 2020

The scope of this report is broader than previous reports, looking not just at suicides, but also deaths by overdose and those occurring because of inadequate access to medical care.

DRNC’s findings are deeply troubling and demonstrate that every year, NC’s jails get more dangerous, especially for people with disabilities. The number of suicides and drug-related deaths, including from overdose or withdrawal, continued to rise. In 2020, North Carolina had a record number of deaths in NC jails. Fifty-six people died due to suicide, illness, or injury in NC jails in 2020, an unacceptable number. In 2020, 32 deaths were suicide or substance use related, up from 30 deaths in 2019, and 22 in 2018.

It is significant that these deaths continued to increase in 2020, a time when some jails took steps to decrease their overall jail populations due to the pandemic. It was also the first year that new regulations were in place to address this alarming rise in suicide deaths.[1]

Death toll linked to insufficient mental health and substance use services

Data reveals that many of the deaths in NC jails were entirely preventable. The people whose stories DRNC shares died because of unsafe conditions and inadequate access to care they desperately needed. Their stories show that many of these people suffered horrific and agonizing pain when they died, suffering that could have been completely avoided with humane attention and care. Most of these people died before they even had their day in court.

NC jails house some of the most vulnerable people in society, including those with acute mental health and substance use disorders. In large part due to NC’s abject failure to invest in community mental health services, many people end up in crisis and are brought to jail rather than proper care facilities. Too many people are caught in the criminal legal system due to untreated or insufficiently treated mental health disabilities and substance use. Despite a needlessly large jail population, DRNC’s urgent appeals for sheriffs and legislators to improve mental health and substance use services have gone largely unheeded – with devastating consequences.

These appalling in-custody deaths are the direct result of NC’s continued failure to improve mental health and substance use services in NC jails. We cannot allow this inhumane suffering and loss of life to continue when there are remedies that can be affordably and effectively implemented.

Jails must address these dangerous trends immediately

The mission of jail leadership and detention officers must evolve to meet the reality that too often, people with disabilities are warehoused in our jails rather than cared for in the community. Without enough prevention and community supports for people with mental health disabilities, it is the police who get called when someone is in crisis, not a mental health professional.

Although jails were not designed to be healthcare facilities, jail leadership cannot ignore this current reality. Jails must be ready to care for people struggling with mental health disabilities and addiction. Jail leadership cannot meet their constitutional duty to provide proper care for people in their custody unless jails develop mental health resources, programming, treatment, and strategies to support the people in their custody.

The current practice of placing people with mental health disabilities and substance use disorders in extremely harsh and punitive settings without the care and treatment they need leads to the predictable loss of life we are documenting. Experts widely accept that the jail environment exacerbates mental health disabilities, heightens vulnerability, and increases the risk of self-harm and suicide.[2] Jail leadership must shift their policies to create a culture that promotes safety and well-being for the people in their custody and the officers who work there.

Regulation of jails

The atrocious conditions confronting people with mental health disabilities who end up in NC jails are further complicated by the way the jails are regulated. There are over 100 jails in NC, and review for compliance with the Jail Rules is assigned to a three-person team at NC Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Division of Health Services Regulations (DHSR). This small team is responsible for conducting over 200 bi-annual inspections of the jails, in addition to complaint and death investigations, and provision of technical assistance.

When the DHSR Inspection Team identifies a violation of the Rules, the sanctions authorized by NC law are weak, with the result that all too often, dangerous conditions go uncorrected for months or years. When a jail fails an inspection, there are no fines levied or immediate consequences for jail administrators. They are not required to quickly address the violations. Only when the Secretary of DHHS determines the failure jeopardizes safety is DHHS authorized to order corrective action or close the jail. However, both of these options require a notice and appeal process that can take months while the dangerous condition remains unchanged.

DRNC has long urged that additional resources are needed for effective oversight of jails. NC needs a fully staffed team of inspectors that can respond to unsafe conditions and events, and provide technical assistance for improvements. When violations are found, quick and meaningful corrective actions must be required.

DRNC recommendations

This 2020 data demands action. These dangerous, life-threatening trends must be corrected. As with our prior reports, DRNC again urges NC jails to adopt active suicide prevention programs. We also recommend the following:

- Pass legislation to provide more transparency about the conditions of NC jails. Currently, only deaths are required to be reported; jails do not have to report the number of attempted suicides and other events resulting in physical and psychological harm. We must pass legislation like House Bill 841 (2021), which would have required jails to report attempted suicides with follow up by the NC DHHS.

- Adequately fund the jail regulation unit at the DHSR. Currently, there are only three inspectors responsible for conducting over 200 inspections per year, two inspections for each jail facility. These three inspectors must also respond to complaints and conduct death investigations across the state. A robust unit would provide oversight of compliance with the regulations and technical assistance to ensure safety in the jails. House Bill 841 (2021) would have added two Jail Inspectors and a Facility Compliance Consultant to DHSR, allowing for greater follow up and technical assistance. That bill did not pass, and DHSR remains understaffed.

- Require the creation of Suicide Prevention Programs that are robust and systematic, rather than targeted to a few people identified at admission as presenting a suicide risk. Effective Suicide Prevention Programs must:

- Run from intake until discharge

- Include enhanced screening and assessment, and not simply rely on self-reporting

- Have robust staff training on suicide prevention, mental health and substance use

- Require all staff to constantly be on alert for signs of suicide risk

- Have adequate medical and mental health staffing

- Limit the use of isolation and increase social support

- Have plans and procedures for transfer to appropriate and safe treatment for at-risk individuals

- Include robust evaluation and internal and external review of each event with staff and offender debriefing

- Provide adequate medical care for incarcerated people, which includes proper clinical oversight and medication when people are experiencing substance use overdose or withdrawal.

- Engage in a community Stepping Up campaign to reduce the number of people with mental health and substance use needs who end up in our jails. Stepping Up Campaigns bring a community together to develop resources and programs to divert people with mental health disabilities from the criminal legal system.

Transparency is critical

While some documentation of jail deaths is required by statute and is considered public record, most of what happens in our publicly funded jails, including many details about these jail deaths, remains a mystery to the public. Often, medical examiner reports or autopsies offer few details about the circumstances surrounding a death. DHSR investigations contain varying amounts of information, are often heavily redacted, and are typically conducted away from public scrutiny. State Bureau of Investigations (SBI) investigations into these deaths are exempt from NC’s public record law and not available to the public.

DRNC tracks information and produces these reports on jail deaths to bring this important information to light. Currently, there are no reporting requirements for suicide attempts, assaults, medical emergencies, or other serious safety concerns. Legislative attempts to increase reporting requirements in the jails have failed.

Timely and accurate data is essential to our communities in charting a path to safer jails. A death in a jail must be thoroughly and publicly investigated. These incidents are often symptoms of unsafe conditions and practices that jeopardize the safety of incarcerated people and jail staff alike. Jails are publicly funded institutions that represent a community’s values and expectations. North Carolinians have an investment in safe jails, and a right to know if their jails are being run safely. Accountability to the public and to the loved ones of not only the people who die and suffer injury, but the countless individuals at risk of meeting the same fate, compels full transparency about serious occurrences, and the corrective actions taken in response.

Transparency is a crucial first step in ensuring accountability in our jails. DRNC is calling for increased transparency.

Discussion

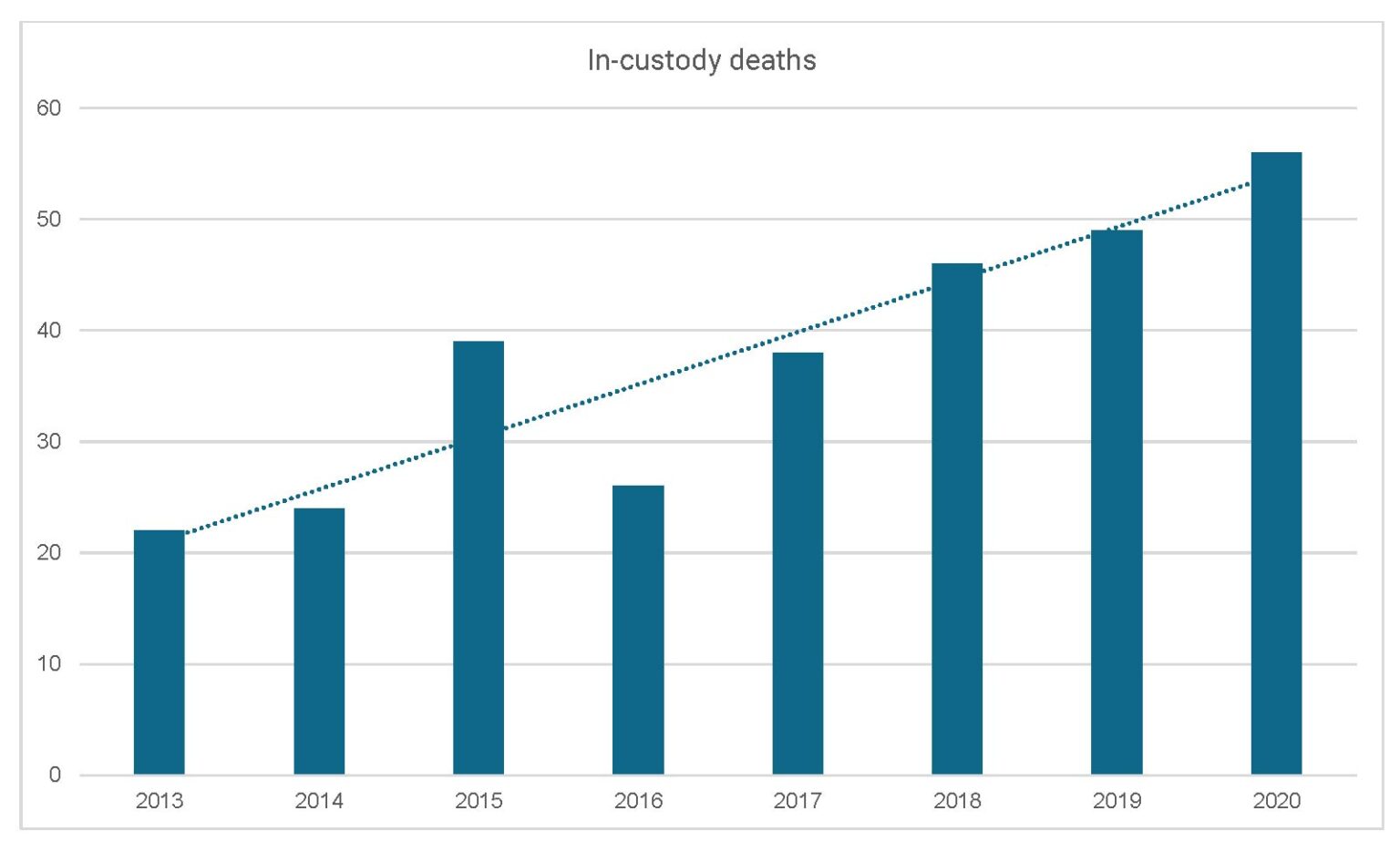

The number of in-custody deaths increased in 2020, as it has every year since DRNC began monitoring jail deaths in 2013, except in 2016.[3]

Table for figure 1: In-custody deaths 2013-2020

| Year | Number of in-custody deaths |

| 2013 | 22 |

| 2014 | 24 |

| 2015 | 39 |

| 2016 | 26 |

| 2017 | 38 |

| 2018 | 46 |

| 2019 | 49 |

| 2020 | 56 |

The fact that 2020’s numbers increased is alarming in and of itself, but this increase in deaths came during a steady decrease in the overall statewide jail population beginning in April 2020 and lasting through November 2020, likely caused by the COVID pandemic and steps taken by some jails to decrease overall population.

Increased number of deaths by suicide

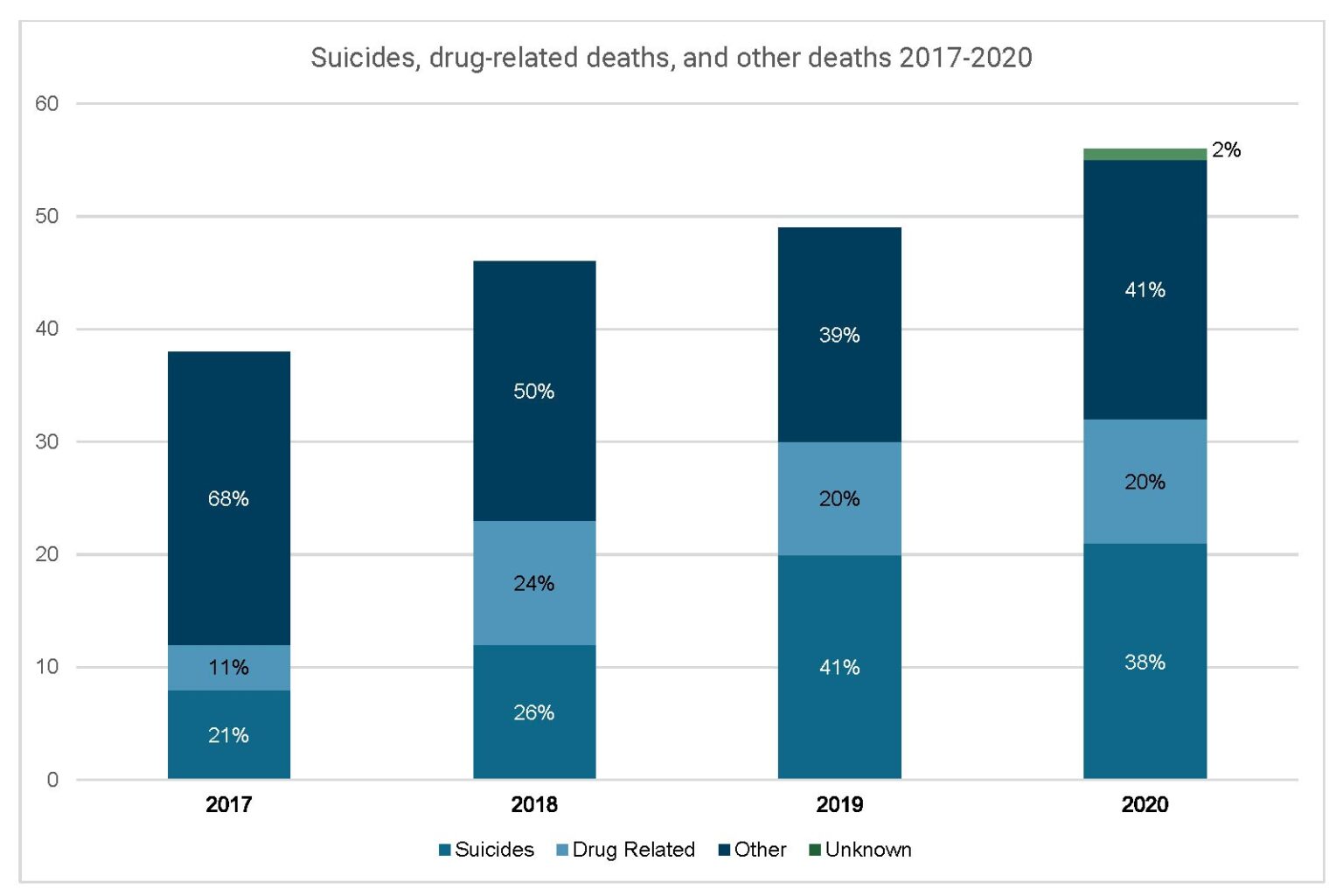

In 2020, suicides in North Carolina jails increased to a record number – at least 21 people died by suicide in our Jails in 2020.[4] This is an increase from the 20 suicide deaths in 2019 and the 12 people who died by suicide in 2018.

Along with increasing numbers of suicides, people also suffered and died in NC jails because of overdoses and withdrawals. These avoidable deaths remain constant despite advances in addiction treatment. The next chart shows a breakdown of the number of deaths by suicide, drug overdoses and withdrawals, and other causes.

Table for figure 2: Suicides, drug-related deaths, and other deaths 2017-2020

| Cause of death | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Unknown | — | — | — | 1 |

| Other | 26 | 23 | 19 | 23 |

| Drug-related | 4 | 11 | 10 | 11 |

| Suicides | 8 | 12 | 20 | 21 |

Percentage of deaths by type

| Year | Suicide and drug-related deaths | “Other” deaths |

| 2017 | 21% | 68% |

| 2018 | 50% | 50% |

| 2019 | 61% | 39% |

| 2020 | 58% | 41% |

Strikingly, the percentage of deaths in the “other” category is on a downward or even trend while the total number of deaths are increasing. Thus, the rise in total deaths is entirely attributable to the increase in suicides and drug-related deaths, which increased from 12 total in 2017 to 32 total in 2020.

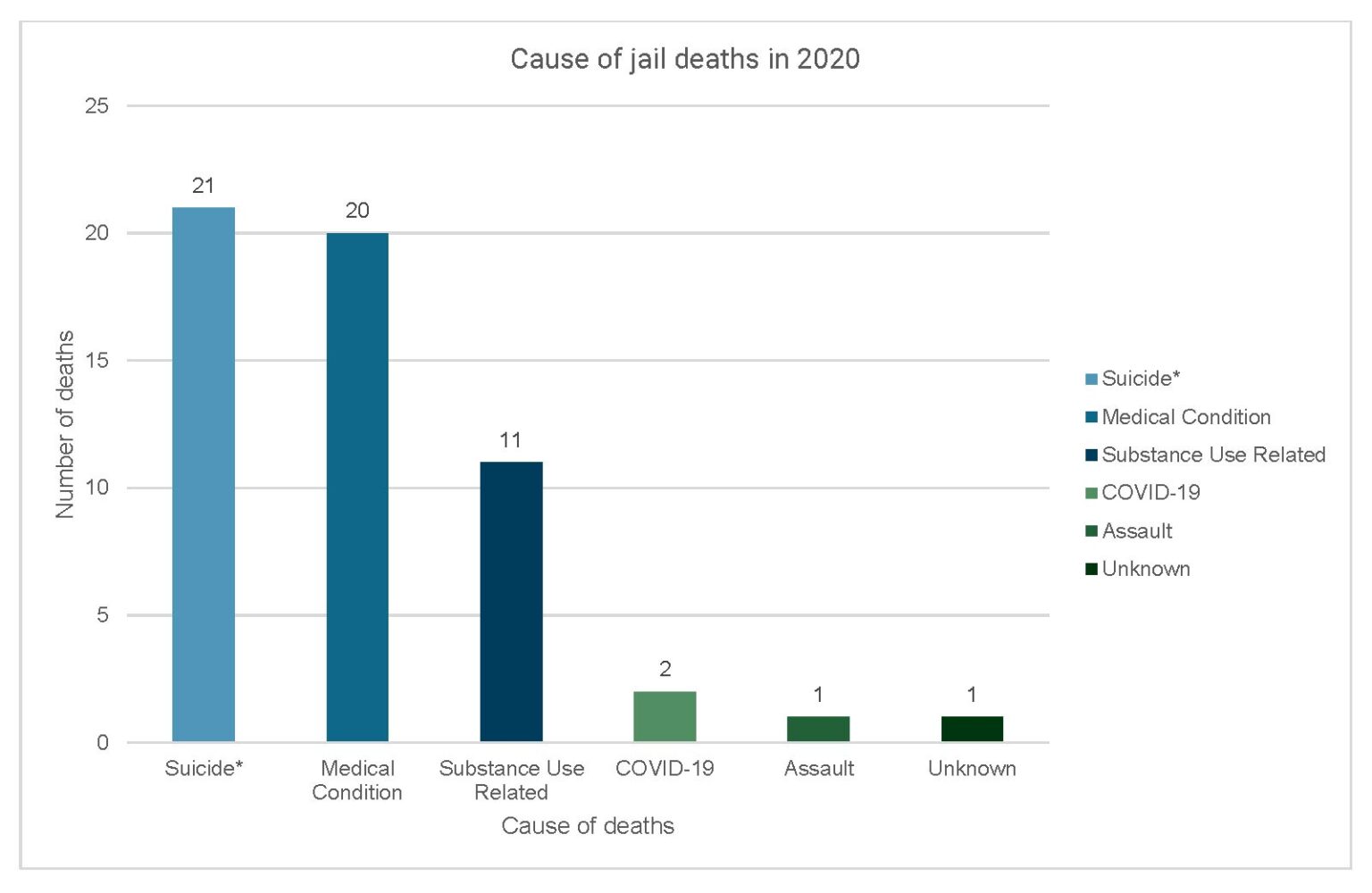

In 2020, suicide was the leading cause of death in NC jails.

Table for figure 3: Cause of jail deaths in 2020

| Cause of death | Number of deaths |

| Suicide | 21 |

| Medical condition | 20 |

| Substance use related | 11 |

| COVID-19 | 2 |

| Assault | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 |

National data shows that NC jails are failing when compared to national and regional trends. NC jails have higher suicide rates compared with the NC general population and the national incarcerated population. Since 2014, the suicide rate[5] in North Carolina jails has been far higher than the suicide rate in North Carolina’s non-incarcerated population.[6] This gap has increased recently, and in both 2019 and 2020, the NC jail suicide rate was around nine times the suicide rate of the non-incarcerated population.[7]

In 2017, the suicide rate in NC jails was slightly below the suicide rate in jails and detention centers nationwide.[8] However, since 2017, the North Carolina jail suicide rate has drastically increased. By 2019, the NC jail suicide rate was more than double the national rate.[9] While there is no available data on the 2020 national jail suicide rate, the NC rate continued to increase.[10]

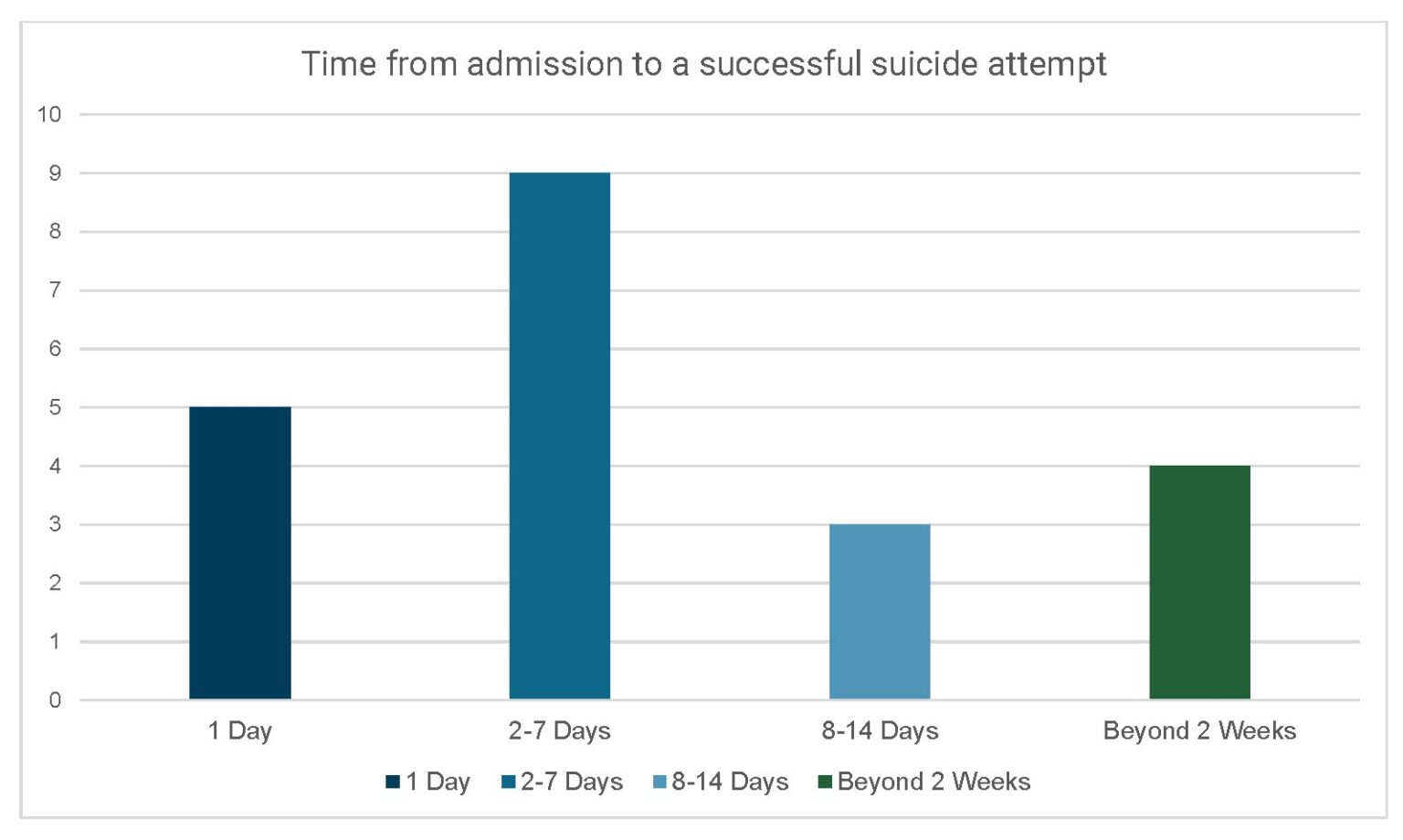

Time from admission to death shows quality screening at admission is critical

Suicides

Over half of suicides in NC jails occurred within one week of admission to the jail. Five occurred within the first 24 hours. Twenty of the 21 suicides were by hanging. The remaining suicide was by jumping from the second tier in a cell block. These numbers and types of deaths illustrate poor implementation of suicide prevention programs.

Failures in screening, supervision, and decisions to take people off suicide watch despite ongoing risk of self-harm continue to persist in NC jails, even though updated jail regulations in 2020 require more robust suicide prevention programs.

Table for figure 4: Time from admission to a successful suicide attempt

| Time from admission | Number of deaths |

| 1 day | 5 |

| 2-7 days | 9 |

| 8-14 days | 3 |

| Beyond 2 weeks | 4 |

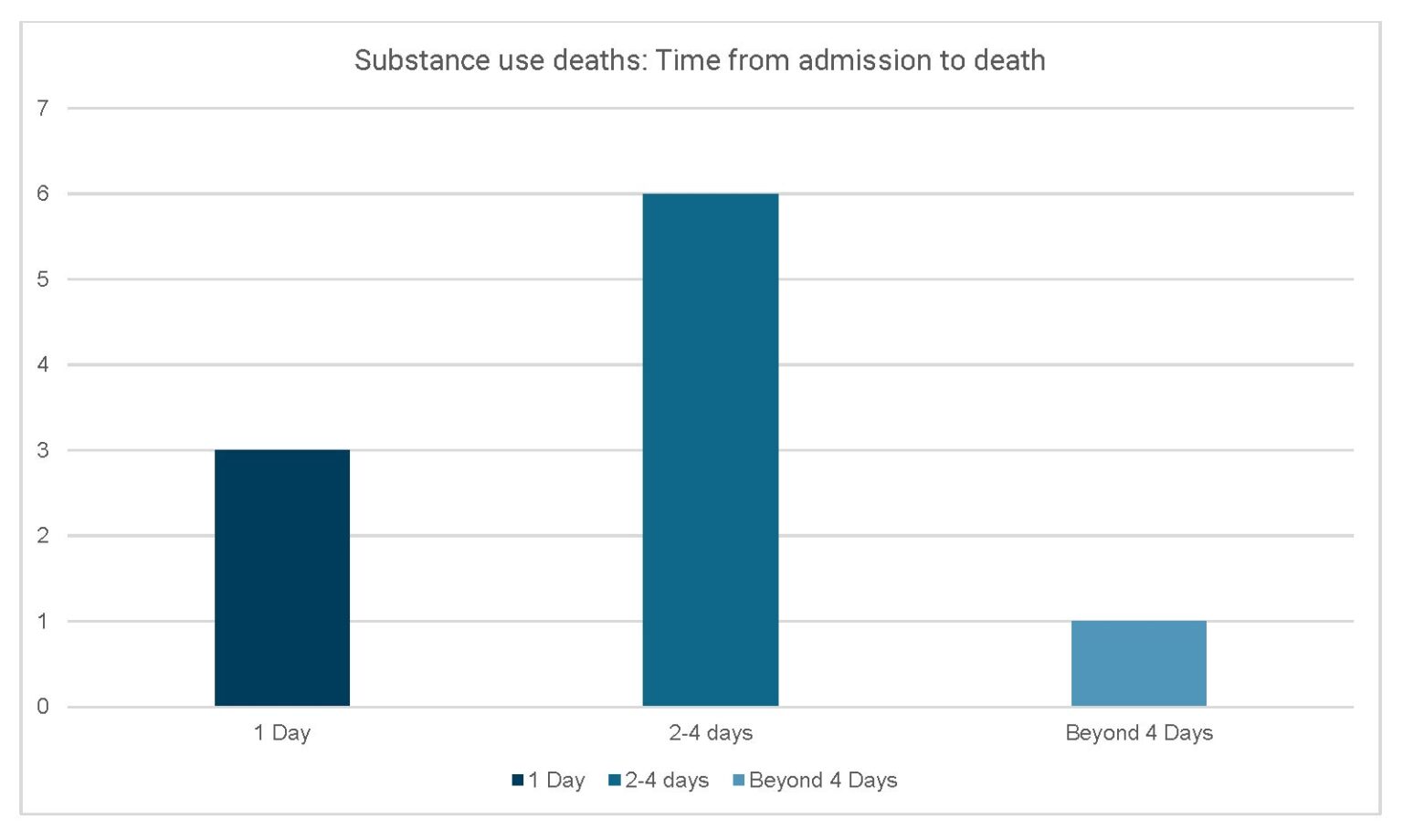

Substance use related deaths

Much like suicides, most of the substance use deaths occurred in the first few days of incarceration. This pattern indicates serious failures to screen and treat people who were in crisis due to withdraw or overdose in jails.

People in jail are at risk of dying from avoidable, substance-related deaths in the first hours and days of incarceration. Policies and staffing must be reformed to provide people in substance use crisis with constitutionally adequate medical care, including competent clinical supervision and medications to prevent these deaths.

Table for figure 5: Time from admission to death from substance use

| Time from admission | Number of deaths |

| 1 day | 3 |

| 2-4 days | 6 |

| Beyond 4 days | 1 |

Accounts of 2020 Jail deaths reveal gaps in care and treatment, and needed reforms

Below, DRNC describes several 2020 jail deaths to illustrate key deficiencies in jail policies and practices that unnecessarily put lives in danger and increase risk and liability for NC counties. These accounts are not isolated examples. Each story exemplifies a pattern of treatment that we have seen across multiple accounts of jail deaths and includes horrific details to demonstrate that this inhumane treatment of incarcerated people is a human rights issue. Readers should use discretion as the stories are potentially traumatizing.

North Carolina’s failure to provide access to mental health and substance use disorder services in NC jails puts people in custody at risk, and these failures often have deadly consequences. This inadequate care and lack of oversight must be remedied.

Failure to directly observe people every 30 minutes

Direct Observation is a strategy to actively manage jails so officers can identify and resolve problem situations quickly.[11] NC has adopted the Direct Observation strategy to ensure a safe and secure jail environment for officers, visitors, and people in custody. In NC, incarcerated people must be directly observed by officers twice an hour on an irregular basis, or four times an hour when people are placed on a Special Watch for safety, often due to unusual behavior, intoxication, or risk of suicide.[12] Actual Direct Observation by detention staff is critical to a safe jail. For years, DRNC and press accounts have documented the dangers from the failure to directly observe people in NC Jails. Proper Direct Observation could have saved the life of KG, described below.

KG’s story

KG, age 36, was the third person to die by suicide in a 10-month period in this county jail. Two days after KG was admitted to the jail, he was restricted to his cell as punishment for a rule infraction. His cellmate was allowed to go to the dayroom. DHSR reports cell block video that shows the following:

- At 2:16 PM KG put a trash bag over the cell window restricting the view inside;

- At 2:21 PM an officer passed the cell conducting a “supervision round” which required the officer to directly observe KG. The officer did not look in the cell window;

- At 2:31 PM an officer walked by the cell door but did not look in the cell window;

- An officer walked by the cell door but did not look in the cell window four more times; at 2:47, at 3:02, at 3:12, and at 3:16 PM.

The officers recorded they conducted “supervision rounds” during this period. Around 3:30 PM KG’s cell mate looked in the cell then approached an officer and asked for someone to check on KG. They proceeded to the cell. At 3:33 PM the officer opened the door and they observed KG partially on the floor hanging from the bunk bed with a sheet tied around his neck. KG died that day.

In light of the cell block video, the Sheriff agreed with DHSR that “the quality of supervision rounds conducted was not sufficient to meet the state standard in 10A NCAC 14J .0601.” The Sheriff was required to submit a proposed corrective action plan. DHSR accepted the plan, in which the Sheriff promised to re-educate his officers and comply with the rules in the future. The Sheriff also wrote that “remedial action” was taken for the officer who was assigned the post.

Failure of suicide screening and suicide watch

DRNC identified two frightening trends when reviewing the 21 suicides that occurred in NC jails in 2020:

- Screening failures; and

- Consistent failure to recognize the risk of suicide.

In our review, DRNC found 5 suicides where the person had recently been taken off suicide precautions, and 13 where the person had undergone and passed suicide risk screening upon admission to the jail.

These numbers, combined with the ever-increasing numbers of suicides in NC jails, illustrate a need for more robust, consistent, and ongoing suicide prevention programs. Experts have long advised that answers to a screening questionnaire are just one point in a suicide prevention program that should include alert staff conducting constant observations for risks.[13] Jails must change their suicide protocols to comply with best practices.

Jail rules require screening whenever someone is admitted to a jail.[14] The purpose of the screening is to identify medical needs and risks to health and safety. When someone is identified at risk of suicide, has attempted suicide in the past, is intoxicated (.15+), is screaming, is laughing uncontrollably, is violent, or is threatening self-harm, they are to be placed on “special watch” rounds.[15] This special watch round requires an in-person check by an officer four times an hour on an irregular basis, with not more than 20 minutes between rounds.[16] The failure to identify medical risks and place a person on special watch can be deadly, as is shown by the accounts below.

HW’s story

Before his arrest, HW, age 58, exhibited suicidal ideation by pouring lighter fluid on himself and attempting to ignite the fluid. He was arrested for attempted arson and domestic trespassing. The jail’s intake process did not identify any risk of self-harm for HW. The autopsy revealed a blood alcohol level of .13. The jail told DHSR that HW’s demeanor was calm and relaxed and there was not an odor of lighter fluid. The detention staff did not place HW on any special precautions. HW was placed alone in a cell. Four hours later he was found hanging by the drawstring of a laundry bag suspended from the bed rail. HW died at a hospital the next day.

DHSR found that the jail should have put HW on a special watch. The rule states: “a previous record of a suicide attempt or a previous record of mental illness shall warrant observation at least four times an hour” (10A NCAC 14J .0601). According to the jail’s Report of Death, 30 minutes passed between the last time staff saw HW alive and when they discovered him in distress.

TK’s story

TK, age 29, was from Virginia. His local County Sheriff had issued a “Missing and Endangered Alert” for TK due to concerning messages he sent a family member. The Virginia Sheriff asked the public’s help to find TK. TK had a history of depression and suicidal ideation.

The next day his car was stopped in North Carolina, and he was booked into the jail at 1:00 PM. He was placed in a single cell. TK was not placed on a special watch. Three hours later, at 4:10 PM, he was found hanging with a towel around his neck tied to the wall vent above the door. “I love You” was written on toilet paper in the cell. He died at the jail.

JB’s story

JB, 48 years old, hung himself after 8 days in jail. During that time, he was housed alone in a cell. According to the Medical Examiner documents, JB had a history of multiple suicide attempts and experienced paranoia, hallucinations and deliriums, and also had a history of substance abuse.

Upon arrest he described fear that kidnappers had threatened to kill him. The jail did not place JB on a “special watch” precaution. JB hung himself by a bed sheet tied to a top bunk railing. The DHSR investigation revealed that several required supervision rounds were not conducted on the day JB died.

Forced withdrawal

Jails are required to screen upon admission for signs of substance use. Forced withdrawal from alcohol and benzodiazepines can be deadly without proper and immediate access to care. Symptoms of withdrawal can include headaches, nausea, tremors, hallucinations, heart palpitations, seizures, and more. Benzodiazepine withdrawal often requires medications to help patients safely discontinue its use and reduce life-threatening withdrawal complications.

The risk of death or other harm associated with forced withdrawal is particularly acute within the first days of incarceration. DRNC found that forced withdrawal, overdosing and drug or alcohol use was often paired with an underlying health condition and resulted in at least 11 deaths in NC jails in 2020.

TM’s story

TM, age 36, was stopped for expired tags and arrested when drugs were found in the trunk of the car. According to the Medical Examiner investigation, he was combative enroute to the jail, described as kicking and flailing around. He arrived at the jail at 3:00 AM and was noted to have calmed down but was sweating and grinding his teeth. He was placed in a holding cell equipped with video/camera monitoring.

Three hours later, jail staff went to check on him and found him unresponsive with seizure-like activity. The jail nurse and EMS were called. TM declined rapidly into cardiac arrest. EMS pronounced TM dead at the jail at 7:20 AM. Postmortem toxicology revealed toxic levels of cocaine and methamphetamine, which was determined to be the cause of death.

AC’s story

AC was 32 years old. She was arrested at 8:10 PM on charges of possession of drugs. AC had a history of depression and drug use. She was put alone in a cell. She was last seen alive at 9:30 PM the next evening. The following morning, she was observed by Detention Staff lying on her bed not moving. Later, an officer entered her cell and discovered her lifeless body. She was pronounced dead in the jail cell at 7:11 AM, 35 hours after entering the jail. The cause of death was fentanyl toxicity.

PP’s story

PP, 34 years old, was booked into the jail at 8:35 AM. He was observed snorting a white powder while in the jail holding cell. At 5:00 that afternoon, he was observed to be in distress. He died at 5:30 PM due to fentanyl intoxication.

AD’s story

24-year-old AD was arrested for DWI and placed in a holding cell around 2:23 AM. She was seen lying on the cot in the cell 70 minutes later and again 67 minutes later. According to the records, at 5:19 AM, an officer attempted to wake her, and another officer entered the cell to check for a pulse. The jail nurse found her unresponsive with her jaw clenched. AD was transported to the hospital where she was pronounced dead at 6:18 AM – 4 hours after she was admitted to the jail. The cause of death was acute pregabalin and ethanol toxicity.

Failure to address the heightened risk of self-harm and suicide for people experiencing opiate withdrawal

Individuals with Opioid Use Disorder often experience debilitating symptoms when undergoing opioid withdrawal—including uncontrolled pain and psychological distress. These symptoms may trigger suicidal ideation, especially during the first week of incarceration.[17] According to a review by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), “[h]alf of all individuals who complete suicide in lockups and detention facilities have a history of substance abuse.”[18] Inadequate treatment of withdrawal in NC jails contributed to the number of suicides in 2020.

JP’s story

According to the Medical Examiner’s investigation, JP had suicidal ideations for three days prior to being found hanging by a bed sheet in his jail cell. The day after he was admitted to the jail, he survived an attempted suicide by hanging. He was transported to the local emergency room where, according to news reports, he said he was withdrawing from heroin and wanted to die. He was returned to the jail.

According to DHSR records and news articles, JP told a clinician his suicide attempt was an effort to get help for his withdrawal from substances. A clinician recommended that he be taken off suicide watch and housed with at least one roommate rather than isolated. The clinician recommended a follow-up in one week. JP was taken off suicide watch; however, due to the jail’s COVID-19 policy, JP was placed alone in a single cell. According to DHSR records, he was seen by medical staff, and he asked when he would “see mental health.” Four days after he was admitted to the jail, JP was again found in distress due to hanging. He was taken to the hospital where he died ten days later.

Deadly consequences: AS’ story

In April 2020, AS, father of four, was arrested for second degree trespassing after breaking a fence and entering a neighbor’s yard, where he was attacked by the neighbor’s dog. His mother reported to the police that it was likely that AS had recently bought drugs. He was taken to a local jail, where he showed clear signs of a mental or drug-related crisis – mumbling, yelling, refusing food or water for hours, and engaging in self-harm. He died strapped into a restraint chair 32 hours after his admission. The cause of death was found to be complications of dehydration due to methamphetamine toxicity.

Failure to screen

DRNC found that medical staff never performed a proper medical assessment during the 32 hours AS spent in the jail. Per jail rules,[19] jails must screen people upon intake for heightened risks, such as drug intoxication and mental health disabilities. Based on the police report, drug overdose was likely. However, AS was never given an initial screening to assess medical risks.

Jail staff stated that AS’ behavior prohibited a proper screening exam. But jail documents indicate there were dozens of opportunities to give AS his legally required medical assessment. During several observation rounds, AS was noted as sitting, lying down, being quiet, or simply walking around his cell. He was also restrained in a chair at least twice, and likely for a significant amount of time, according to records. Records did not explain jail medical staff’s failure to give AS a proper screening while he was restrained.

Failure to observe

Review of jail observation records show that jail staff failed to meet their own observation standards. Jail staff regularly failed to observe AS four times an hour, as is required for people exhibiting symptoms of a potential overdose or mental health crisis. Records also indicate that jail staff failed to observe AS every 15 minutes while he was in restraints. Indeed, it appears staff often allowed 20 minutes or more to go by between observations while AS was restrained.

Failure to provide care

Over the 32 hours that he was in jail before his death, AS was only seen by a nurse 4 times before being found unconscious in his restraint chair. A paramedic who was called into the jail to respond to AS’s self-inflicted wounds and other injuries found him unconscious in the restraint chair. Despite spending 32 hours in the jail, AS was only seen by a nurse between the hours of 9am and 3pm. There is no indication that AS was ever assessed or given medical care for a potential methamphetamine overdose, despite his odd behavior and his mother’s report of possible drug use. There is also no indication AS was ever given any mental health care.

While records are not entirely clear, it is likely that AS spent at least 6 consecutive hours in a restraint chair. He was placed in restraints twice during his incarceration. According to these records, AS spent more than 3 hours in restraints before being seen by a nurse and was only seen twice while in restraints. There is no indication a physician was ever involved in AS’s medical care, including the decision to subject him to dangerous restraints. When he was found unconscious in the restraint chair by EMS, AS had not seen a nurse in nearly 18 hours.

Failure to transfer to a higher level of care

Records indicate that AS was offered water only six times during his 32 hours of incarceration. He refused each time. However, despite jail staff being aware that AS had neither eaten nor had anything to drink for 32 hours, they did not medically intervene until he was found unconscious in his restraint chair, dying of dehydration. By the time he died, AS had not been offered water for over 18 hours.

Conclusion

NC’s community mental health system is badly broken. As a result, people with disabilities are treated as criminals and end up in our jails. NC jail death rates are rising every year. Many more people are injured and psychologically harmed by days and months confined without appropriate care and treatment. This is a crisis NC can no longer ignore – the very lives of our friends and loved ones hang in the balance.

Appendix 1

Failure to provide timely and adequate medical services

Jails are constitutionally required to provide an adequate level of healthcare to people in their custody.[20] Required healthcare includes medications, screening measures, and transfer to outside hospitals when the patient needs care beyond the capacity of the jail. In reviewing the 56 deaths in 2020, DRNC found that jails too often failed to recognize serious health concerns, failed to react appropriately to serious medical emergencies, and failed to transfer patients to other facilities when necessary to save their lives.

HH’s story

Jail staff knew that HH was in poor health directly before his death in October of 2020. He was in his 60s, blind, diabetic, and had open sores on his feet. It is unclear why HH was not moved to a hospital or a state prison medical facility, as his disability made him a low security risk. Open sores are serious infection risks in people with diabetes. Per investigative documents, jail staff checked on HH at midnight. When they checked again an hour and a half later, HH was dead in his cell. The cause of death was cardiovascular disease with diabetes.

WH’s story

WH, a 40-year-old man, fell in the shower in August of 2020. According to records, nurses thought he had fainted. He fell again in his cell around 8:30 the next morning. The jail nurse thought he was dehydrated. Later that day, he was found sitting next to the toilet in his cell, surrounded by black fecal matter, with toilet paper stuffed up his rectum and a black substance from his forehead to his neck. He died of a severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The autopsy states that WH’s bleeding had been occurring “for some time.” Despite having two unexplained unconscious falls in a short period of time, he was only offered water for his condition.

JN’s story

JN had a long history of heart conditions when he was admitted to a local jail in November 2019. He had a congenital condition that required surgery at age 5. While in jail, he developed fevers and was placed into a solitary cell. Over the next two weeks, he was left in a solitary cell. His fevers then changed to chest pain. Several weeks after the fever’s onset, he was finally transferred to an outside hospital. He died two days later. The cause of death was sepsis secondary to endocarditis due to congenital aortic stenosis.

FW’s story

FW had a documented history of cardiac disease, including hypertension and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease when he was admitted to a local jail in September 2019. He had undergone coronary artery bypass heart surgery in 2003. On the day of his death in April 2020, he twice complained of chest pains. Despite FW’s high risk for cardiac events and his “significant cardiac history,” jail nurses gave him omeprazole, an over-the counter antacid. He died in his sleep that night of a “cardiovascular event.”

Appendix 2

Counties held accountable in civil lawsuits

When jails fail to meet their duty to provide humane care and treatment, families can seek to hold them accountable with a civil wrongful death lawsuit. Recent substantial settlements in NC jail deaths are reported below. DRNC urges counties to invest in training and personnel to avoid tragic deaths, as well as costly lawsuit settlements after a family’s loved one has died.

Buncombe County

In January 2020, the US District Court for the Western District of NC approved a $2 million settlement to be paid by Buncombe County for the 2017 wrongful death of Michele Quantele Smiley, a 34-year-old mother of six. Smiley died in the jail due to a severe drug overdose that the jail staff observed, but then failed to provide medical care.

Jackson County

In 2019, Melissa Middleton Rice, 49, was arrested following a traumatic domestic dispute. She died by suicide after being left alone without observation in the jail booking area. In November 2021, the County agreed to pay $725,000 to settle the family’s wrongful death lawsuit.

Cherokee County

In November 2021, the County’s insurance company agreed to a $1.8 million settlement to the child of Joshua Shane Long, 31, after his 2018 death in the county jail due to acute methamphetamine toxicity. The lawsuit alleged that jail staff failed to screen Mr. Long for medical problems, failed to provide medical care, and failed to send him for emergency treatment.

Wayne County

In July 2020, Wayne County entered a $985,000 settlement in a civil rights case arising from the wrongful death of Graydon Jerome Parker, III, age 54, in the jail. Mr. Parker was in an acute manic state and experiencing a psychiatric emergency when he was arrested. The detention officers and nursing staff did not obtain any medical treatment for him. Instead, he was pepper-sprayed, stripped naked, and placed in a segregation cell for nine hours. He experienced sudden cardiac arrest and later died due to blunt force trauma, pepper spray, multiple taser applications, and positional asphyxia while being held in a prone position.

Cleveland County

In 2021, Cleveland County settled the lawsuit filed by Jeffery Todd Dunn’s family for $347,500. In 2019, jail staff placed Mr. Dunn in a cell with another inmate and failed to monitor them regularly. Mr. Dunn’s cellmate killed him. This was the second wrongful death settlement for Cleveland County; in 2019, the County settled a lawsuit for $303,000 for the 2015 death of Mr. Archie McNeilly, Jr., 40, who died of renal failure.

Appendix 3 – Jail deaths demographics

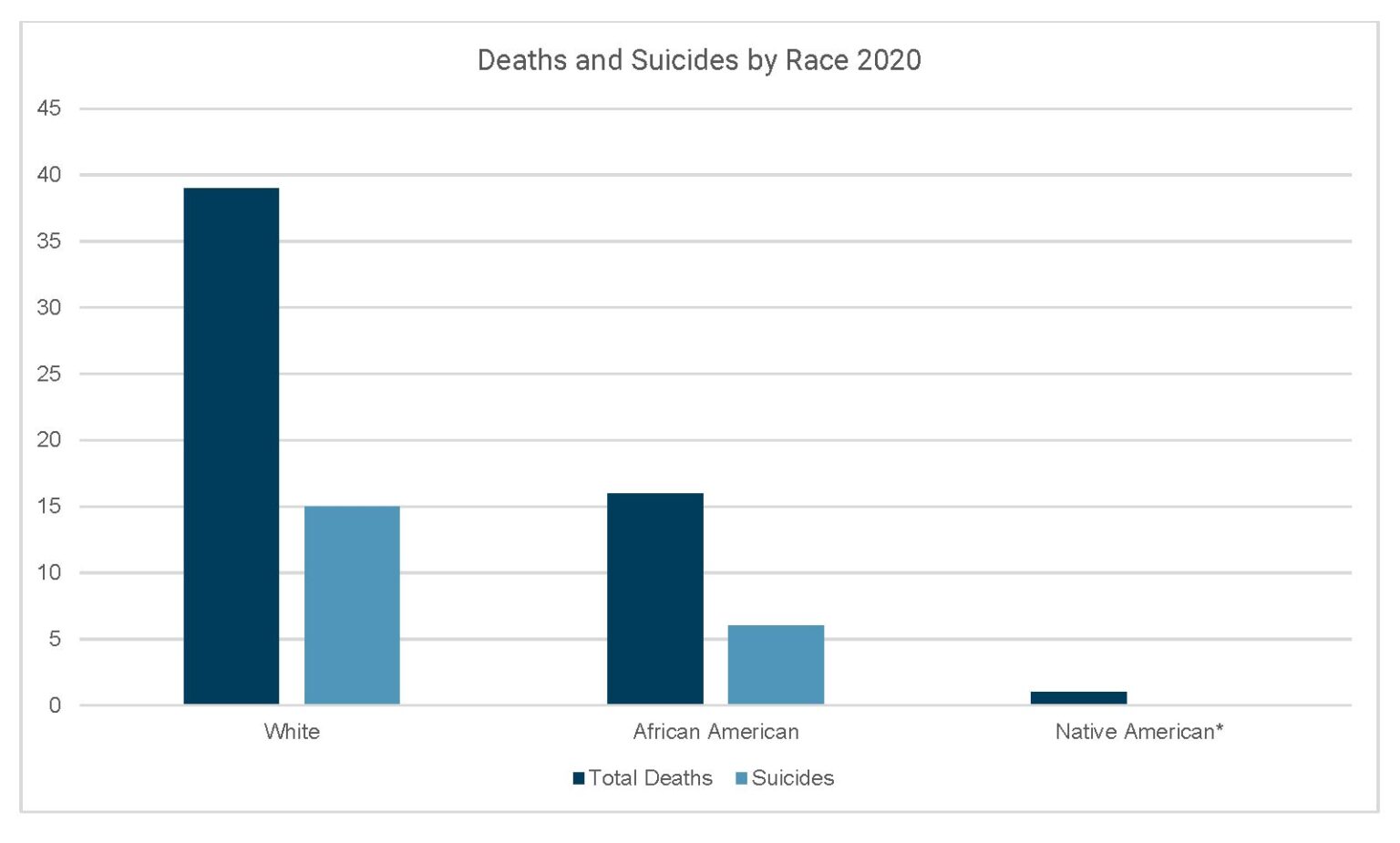

Race

Table of figure 6: Total deaths and suicides by race

| Race | Total Deaths | Suicides |

| White | 39 | 15 |

| African American | 16 | 6 |

| Native American* | 1 | — |

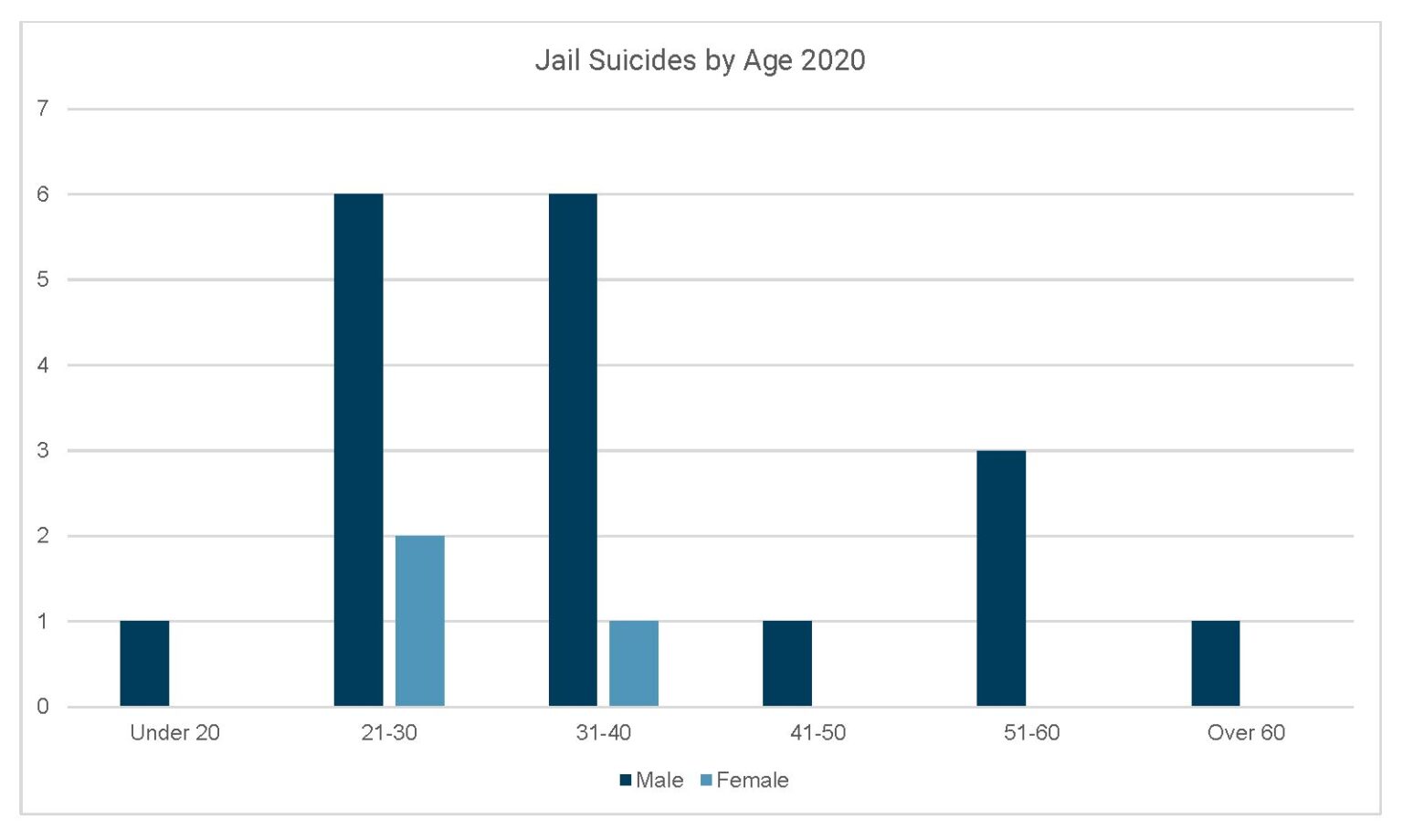

Age

Table of figure 7: Jail suicides by age 2020

| Age | Male | Female |

| Under 20 | 1 | 0 |

| 21-30 | 6 | 2 |

| 31-40 | 6 | 1 |

| 41-50 | 1 | 0 |

| 51-60 | 3 | 0 |

| Over 60 | 1 | 0 |

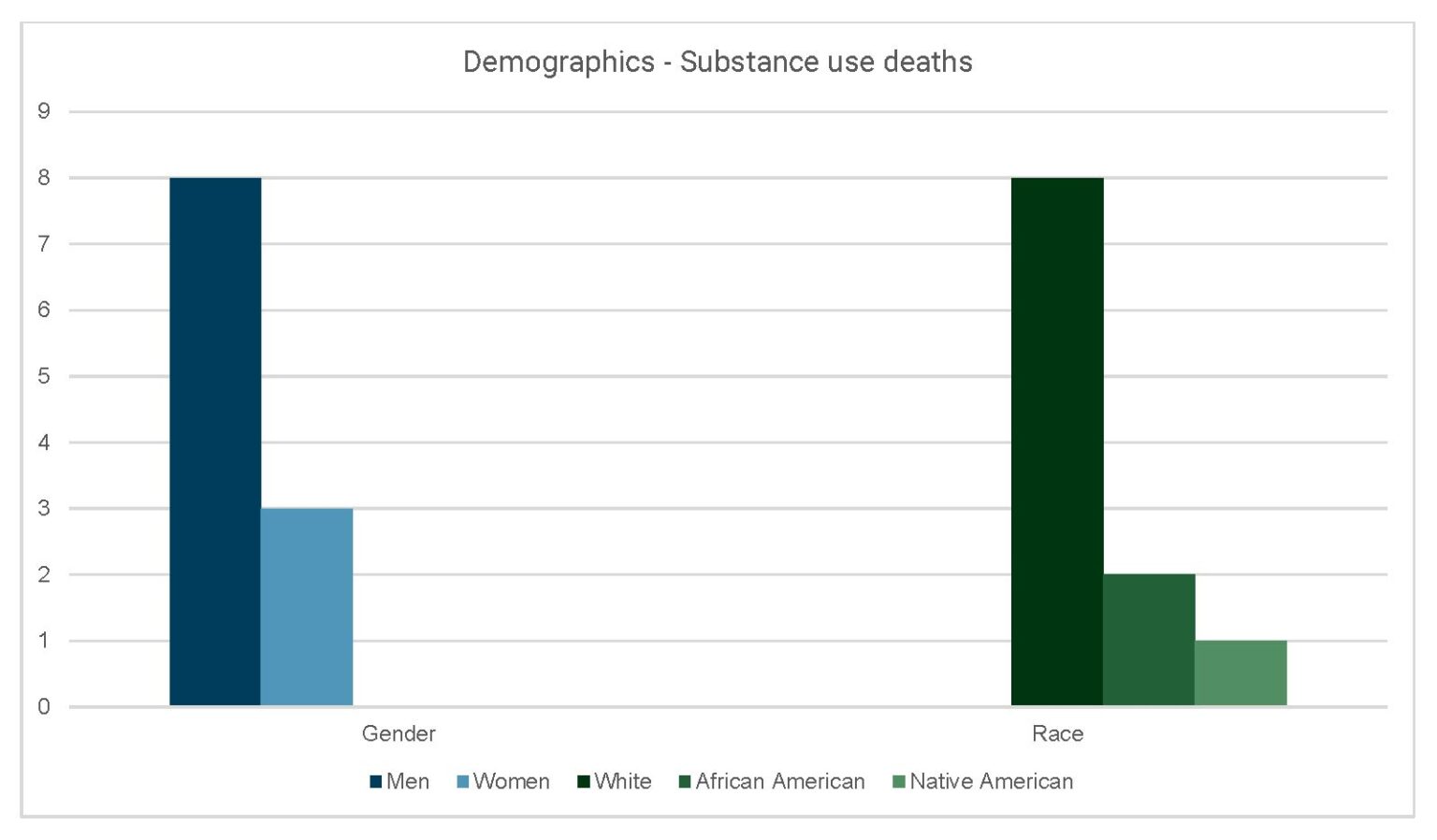

Demographics of substance-use deaths

Table of figure 8

| Gender | Race | |

| Men | 8 | |

| Women | 3 | |

| White | 8 | |

| African American | 2 | |

| Native American | 1 |

Appendix 4

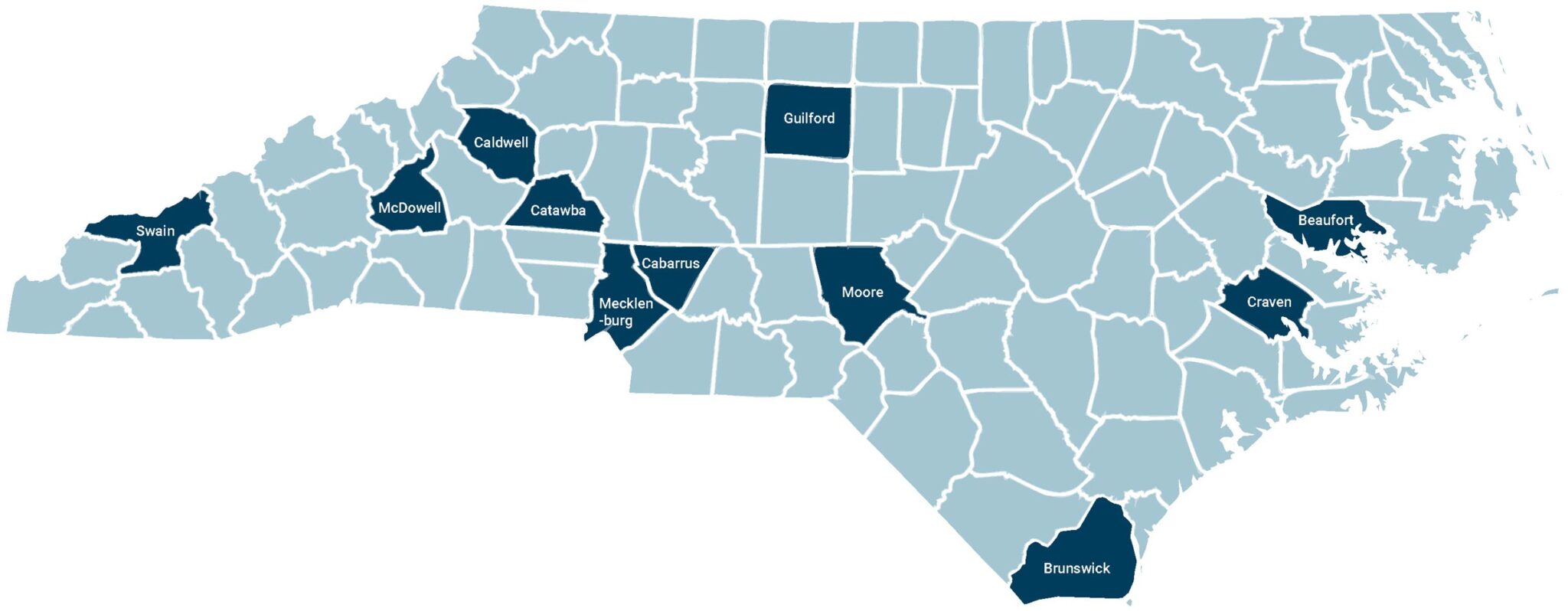

Counties with substance use deaths

- Brunswick

- Caldwell

- Mecklenburg

- Cabarrus

- Swain

- Beaufort

- Guilford

- Catawba

- Craven

- Moore

- McDowell

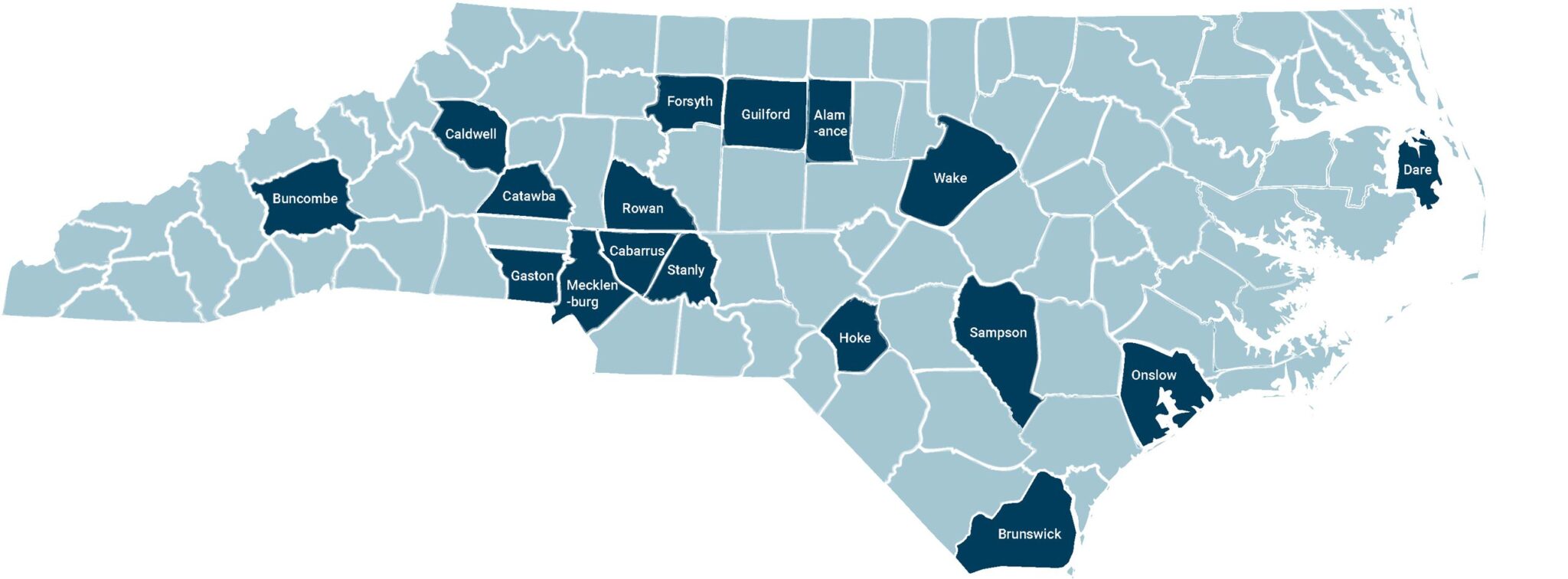

Counties with suicide deaths

- Alamance

- Guilford – 2 suicides – one in the High Point Jail and one in the Greensboro Jail

- Stanly

- Cabarrus

- Sampson

- Wake – 3 suicides

- Gaston

- Forsyth

- Buncombe

- Hoke

- Rowan

- Caldwell – 2 suicides

- Brunswick

- Catawba

- Onslow

- Dare

- Mecklenburg

Printable PDF: 2020 Deaths in Jails Report

Endnotes

[1] NC statutes declare that jails “be operated so as to protect the health and welfare of prisoners and provide for their humane treatment” (NCGS 153A-216). The Jail Rules establish minimum statewide standards intended to protect the health and welfare of people in our jails (Subchapter 14J – Jails, Local Confinement Facilities, 10A NCAC 14J). In 2020, after years of advocacy by DRNC and other advocates, the Jail Rules were updated to add important safety provisions including that every jail have a suicide prevention program and provide routine medical care in addition to emergency response.

[2] National Study of Jail Suicides: 20 Years Later, US Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections (2010).

[3] All data and information gathered for this report are public record. DRNC requests all available public records of jail deaths from both NC DHHS and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. These documents include a Death Report, Medical Examiner Investigation, Autopsy, Toxicity Screen, and DHSR death investigations for each death that occurs. By statute, these agencies are required to investigation whenever a person dies in the custody of a jail or local confinement facility. We also relied on articles in the media and obituaries.

[4] We report “at least 21” people died by suicide in our jails in 2020 because at this time the NC Medical Examiner reports for two deaths are still incomplete.

[5] Suicides per 100k persons.

[6] Mortality in Local Jails, 2000-2019, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (December 2021); Suicide Mortality by State, Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics (accessed 3/16/2022); NC Jail and Local Confinement Occupancy for 2018, UNC School of Government (2020); NC Jail and Local Confinement Occupancy for 2019, UNC School of Government (2020); 2021 Confinement Tool, UNC School of Government (2021); NC Suicide data gathered by DRNC through public records.

[7] NC Jail and Local Confinement Occupancy for 2019, UNC School of Government (2020); 2021 Confinement Tool, UNC School of Government (2021); Suicide Mortality by State. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, (accessed 3/16/2022). NC Suicide data gathered by DRNC through public records.

[8] Mortality in Local Jails, 2000-2019, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, (December 2021). NC Suicide data gathered by DRNC through public records.

[9] Mortality in Local Jails, 2000-2019, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, (December 2021); NC Jail and Local Confinement Occupancy for 2019, NC School of Government (2020); NC Suicide data gathered by DRNC through public records.

[10] 2021 Confinement Tool, UNC School of Government (2021); NC Suicide data gathered by DRNC through public records.

[11] National Institute of Corrections, Strategic Inmate Management. “Direct supervision jails focus on actively managing inmate behavior to produce a jail that is safe and secure for inmates, staff, and visitors.”

[13] Guiding Principles to Suicide Prevention in Correctional Facilities, Lindsay M. Hayes © National Center on Institutions and Alternatives (2011); See also: Suicide Prevention Resources for Adult Corrections, Suicide Prevention Resource Center (May 2017).

[17] See US DOJ Investigation of the Cumberland County Jail (Bridgeton, New Jersey, 2021). “At the CCJ, inadequate treatment of opiate withdrawal contributed to several inmates’ suicides. With respect to the seven suicides at the CCJ since 2014, at least six of those inmates were opiate users, and the evidence uncovered in our investigation suggests that those six inmates were experiencing opiate withdrawal at the time of their suicides.”

[18] Am. Psychiatric Assoc., Psychiatric Services in Correctional Facilities, 38 (3rd ed. 2016).

[20] NCGS 153A-221, NCGS 153A-225; 10A NCAC 14J .1001; Estelle v. Gamble, 429 US 97 (1976).