“Stop Torture in NC’s Prisons”: Part 2

In our first installment in this series, we described how long-term solitary confinement in NC prisons is torture and that it must stop. But who is punished with long-term solitary confinement?

The answer to this question reveals another sinister and abhorrent aspect of this tortuous practice: There are clear racial disparities in who suffers long-term solitary confinement.

People of color are punished with solitary confinement more frequently and for longer periods of time than their white counterparts.

Let’s take a look at the numbers that confirm this disturbing finding.

Disparities Deeply Embedded in System

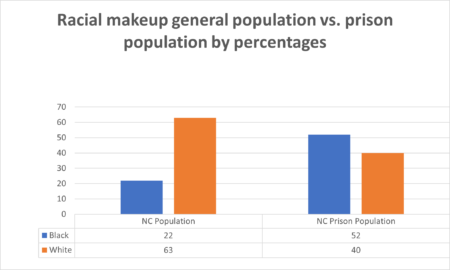

Data shows racial disparity is deeply rooted in NC’s criminal justice system as a whole. In 2019, nearly 63 percent of NC’s population was white, compared with 22 percent who were Black. In contrast, 40 percent of NC’s prison population was white, compared to 52 percent Black.

Fig. 1

We can see from this figure that there is a strikingly disproportionate number of Black people who are incarcerated compared to the overall Black population. This disparity is so significant that in June 2020, the Governor appointed a task force, the NC Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice (TREC), to examine the implications of race in our criminal justice system and to recommend solutions to stop discriminatory law enforcement and criminal justice practices and hold public safety officers accountable.

The TREC’s report and recommendations came out in December 2020 and recommend an examination of the use of solitary confinement in NC.

Data Highlights Significant Disparities

The data cited in the TREC report is deeply disturbing and requires swift action. It shows that after incarceration, disparities in treatment of Black and white prisoners intensifies significantly, including who gets sent to solitary confinement.

NC DPS has several custody designations that meet the definition of solitary confinement (22-24 hours a day). While all of these designations are long-term solitary confinement, there are some differences in the few privileges people are allowed, such as:

- Visitation and phone use

- How long people can stay in solitary before DPS must review their placement

- Use of restraints during exercise

- Items that can be purchased in the canteen

- Permission to eat outside of cell

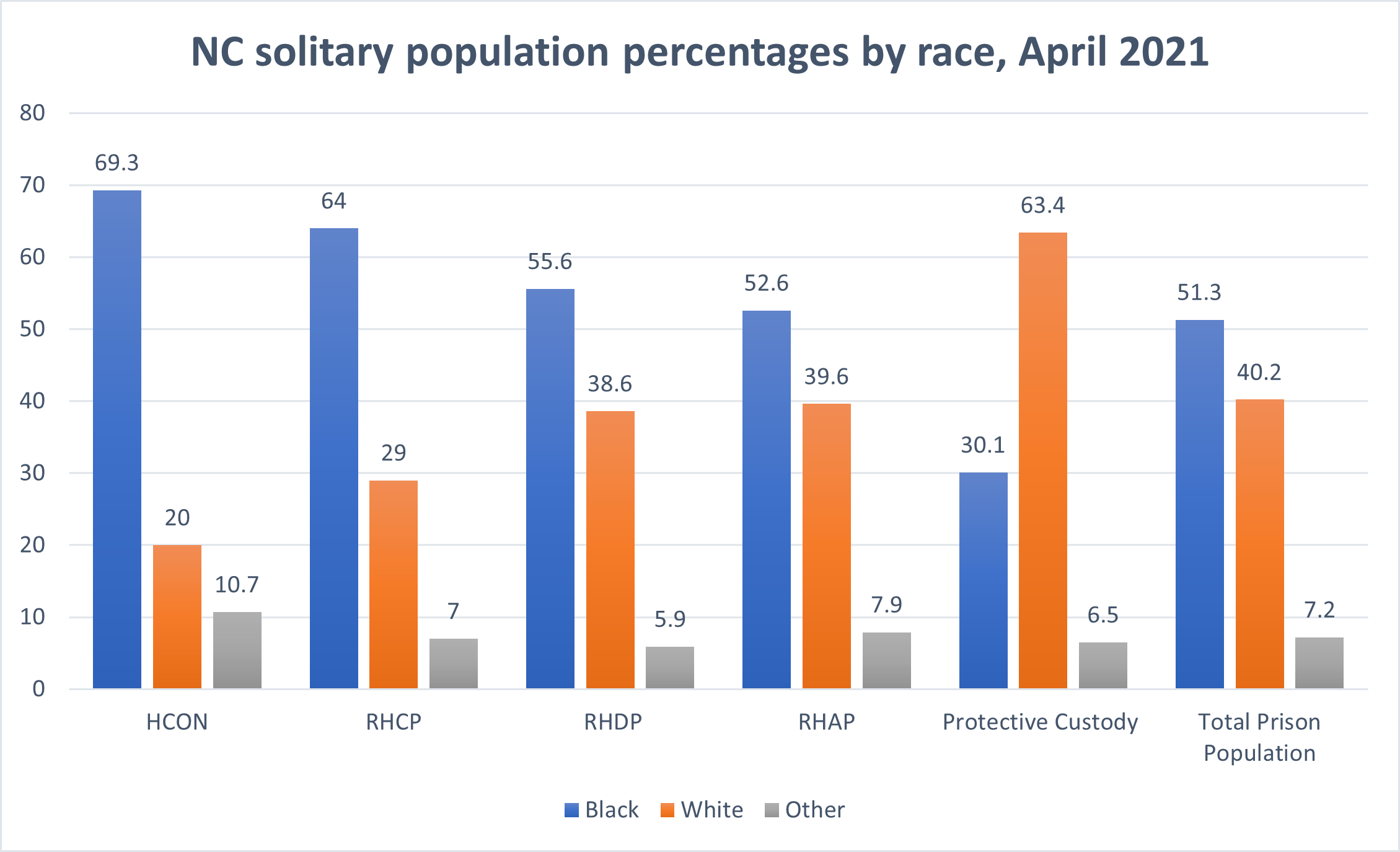

NC DPS data reveals that as restrictions in solitary classifications increase, so do the numbers of incarcerated people of color in these more restrictive settings. In addition, the length of time people spend in solitary increases as the solitary classifications become more restrictive.

For example, in High Security Maximum Control (HCON), the most restrictive and severe level of solitary confinement, 80 percent of the population are people of color, far above the percentage of incarcerated people of color overall in prison, which is 60 percent. The next most restrictive classification of solitary is Restrictive Housing for Control Purposes (RHCP), where 71 percent of that population are people of color, again, far higher than the overall people of color prison population.[1]

Fig. 2

In fact, you can see from this figure that the only type of solitary confinement that is made up of predominately white incarcerated people is Protective Custody – a classification designated to keep those in Protective Custody safe. There, white incarcerated people comprise 63 percent of the population, while 37 percent are people of color. Protective custody is the only long-term solitary custody classification that allows eating meals outside of the cell and has no restrictions on visitation.

Invisible Animus – Implicit Bias

So how do we explain the disproportionate number of Black incarcerated people in solitary confinement? Numerous scientific studies and research suggest this is implicit bias at work (see below for resources on implicit bias). Implicit bias is a psychological phenomenon that explains how people perceive and interpret the behaviors and even the personhood of others.

The TREC report defines implicit bias as “Unconscious attitudes, reactions, stereotypes, and categories that affect behaviour and understanding.” Put simply, because of the human mind’s innate ability to recognize patterns and assess risk, people sub-consciously absorb social stereotypes. We then apply these stereotypes to real-life situations without any awareness this is happening.

Implicit bias, also known as unconscious bias, affects everyone. It is how we make sense of the world around us.

Racial implicit bias causes significant harm and perpetuates systemic racism. Studies have shown that people are affected by racial implicit bias without knowing it, and often in ways that cause them to perceive people of color, and particularly Black men, as more dangerous or criminal than white counterparts.

Because DPS disciplinary decisions can be affected and swayed by implicit bias, we must ensure that the punishments meted out by the disciplinary system do not include torture. The only way to do this is to abolish long-term solitary confinement. Otherwise, there will always be a risk that North Carolina is meting out torturous punishments due in part to implicit racial bias, and the disparities we see in custody classifications will continue to exist.

TREC recommendation regarding implicit bias

The TREC report notes implicit bias permeates all segments of the state’s criminal justice system, including DPS’s system of discipline and use of solitary confinement. It recommends system-wide examination and training, including for prison staff, to address racial bias:

Recommendation No 105: Establish a committee with experts from NCDPS, academia, and community and advocacy groups, including those with lived experience in restrictive housing, to monitor and collect data concerning infractions and the use of Restrictive Housing-Control status and to report annually to the General Assembly on the number, ages, race, custody classification, and control status of prisoners for each unit in every institution, as well as duration and information on transfers from segregation to mental health treatment units.

DRNC supports this recommendation. We also support the TREC’s recommendation to eliminate the use of long-term solitary confinement altogether. We ask you to join us in our advocacy work around this important issue.

What’s next?

This piece is part two of a series examining the use of solitary confinement in NC’s prisons. Stay tuned for more segments in this series: How the racial breakdown looks for incarcerated people ages 18-21; policies that affect prison staff decisions about sending incarcerated people to solitary; and what we can do to stop the use of long-term solitary confinement.

Sign up to receive news and alerts from our Stop Torture in NC Prisons campaign.

Footnotes

- Data current as of 4/17/2021 per DPS website. https://webapps.doc.state.nc.us/opi/downloads.do?method=view

Learn more about implicit bias

These resources include studies and fact sheets about the role implicit racial bias plays in our criminal justice system.

Resources

Fact sheet on racial bias from Justice Research and Statistics Association

Information on implicit bias from the US DOJ’s Community-Oriented Policing Services and Trust and Justice

An Overview of Implicit Bias from Equal Justice Society

https://equaljusticesociety.org/law/implicitbias/

The National Implicit Bias Network

Implicit Bias Aptitude Test Explained – Simply Psychology

Studies

Eberhardt, J. L., Davies, P. G., Purdie-Vaughns, V.J., & Johnson, S. L. (2006). Looking deathworthy: Perceived stereotypicality of Black defendants predicts capital-sentencing outcomes. Psychological Science, 17(5), 383-386.

Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, & Davies, P. G. (2004). Seeing Black: Race crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 876-893.

Goff, P. A., Eberhardt, J. L., Williams, M., & Jackson, M. C. (2008). Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 292-306.

Richardson, L. S., & Goff, P. A. (2013). Implicit Racial Bias in Public Defender Triage. Yale Law Journal, 122, 13-24.